Weightlifting 101: The Squat

The squat is the foundation of movement. It is one of the 7 primal pattern motions. A good squat prepares you for life. A bad squat can wreck your body. Meticulously learning the technique of doing a squat has an immense return of investment on your life quality.

We sit.

Sometimes, we sit all day.

Sitting is quite old— but the way we sit has changed.

Today we sit on chairs, in cars, on computers, while eating, while watching TV, while working. We sit and we sit just to go somewhere sitting to go sit again.

But back then, before the invention of chairs, we sat too, but a little different.

We squatted. That was our resting position.

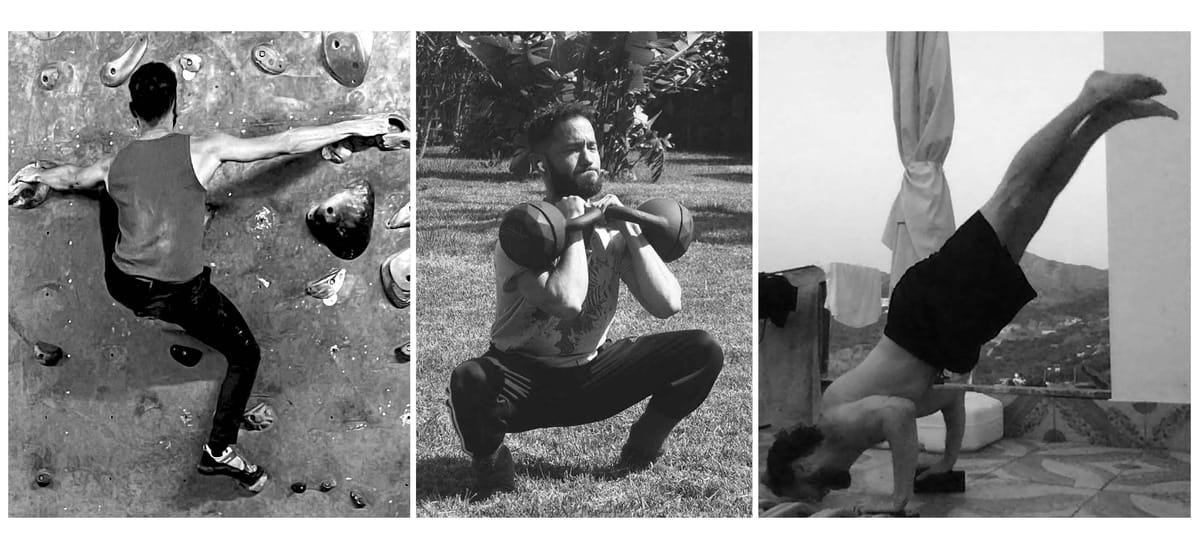

Squats are one of the 7 primal pattern movements we explored in the earlier loveletter episode. We have been doing this probably since we have legs. Today, we will go into the details on how to execute squats properly and practical tips to prevent injuries.

en(dot)wikipedia(dot)org/wiki/Squatting_position

The squat—king of all exercises or the wellspring of countless injuries?

It depends on how you approach it. Let’s demystify the squat and make it your most powerful tool for building a resilient body.

Why Squats Matter

Squats are hailed as the “king of exercises” for their ability to build strength and size in the lower body. Few movements engage as many muscles as this one does.

It’s a cornerstone of the structural integrity of your body.

In the end, you hopefully will benefit from a stable and long term relationship with this beautiful exercise.

Beyond aesthetics, squats improve functional strength, stability, and mobility.

But this famous exercise can also cause harm.

Poor technique, improper bar placement, or insufficient mobility often result in pain or injury, especially to the neck and spine. But with proper guidance, squats can become the safest and most effective exercise in your routine.

Beyond the obvious benefits of doing squats properly like increased cardiovascular health and calorie burn, there is also other benefits you might want to know:

- Functional Mobility: Improves joint flexibility and movement for daily tasks.

- Athletic Performance: Enhances power, sprint speed, and vertical jump.

- Bone Density: Increases bone strength, reducing osteoporosis risk.

- Hormonal Boost: Stimulates testosterone and growth hormone production.

- Core Stability: Strengthens the core for better posture and balance.

- Balance and Coordination: Reduces fall risk by improving proprioception.

- Injury Prevention: Strengthens ligaments and reduces joint injuries.

- Better Posture: Reinforces spinal alignment and combats imbalances.

What is a Squat?

A squat is a fundamental human movement—it’s a primal pattern of sitting, standing, and lifting that engages the entire body. In weightlifting, the squat is a compound movement, meaning it works multiple joints and muscle groups at once.

At its core, a squat involves:

- Lowering the Body: Bending at the hips and knees, so you are hinging, while keeping the chest upright.

- Achieving Depth: Squatting until the thighs are at least parallel to the floor (or deeper, depending on mobility and goals). There is also the concept of “Ass to grass”, which means resting at the depth of the movement and letting your glutes as near to the ground as possible)

- Driving Up: Pushing through the feet and pushing your hip through your centerline to return to a standing position.

Following video is an example of Valentina doing a proper squat. It's not perfect, but it's good enough for the beginning.

Squats train the lower body, engaging muscles such as:

- Quadriceps (front of thighs) – extend the knees.

- Hamstrings (back of thighs) – support knee flexion and hip extension.

- Glutes – drive the hips upward.

- Calves – provide ankle stability.

- Core and Lower Back – stabilize the spine throughout the movement.

While the squat is a natural movement, executing it with heavy weights requires precision. Improper technique can lead to unnecessary strain on the knees, lower back, or spine—which is why selecting the right squat variation for your body mechanics is essential.

But before we dive deep, I will tell you why doing squats not only grows the above mentioned muscles groups.

As mentioned, doing squats stimulates testosterone and growth hormone production greatly, because in almost no other exercise so many muscles are involved.

This hormone boost also let’s other muscles in your body grow.

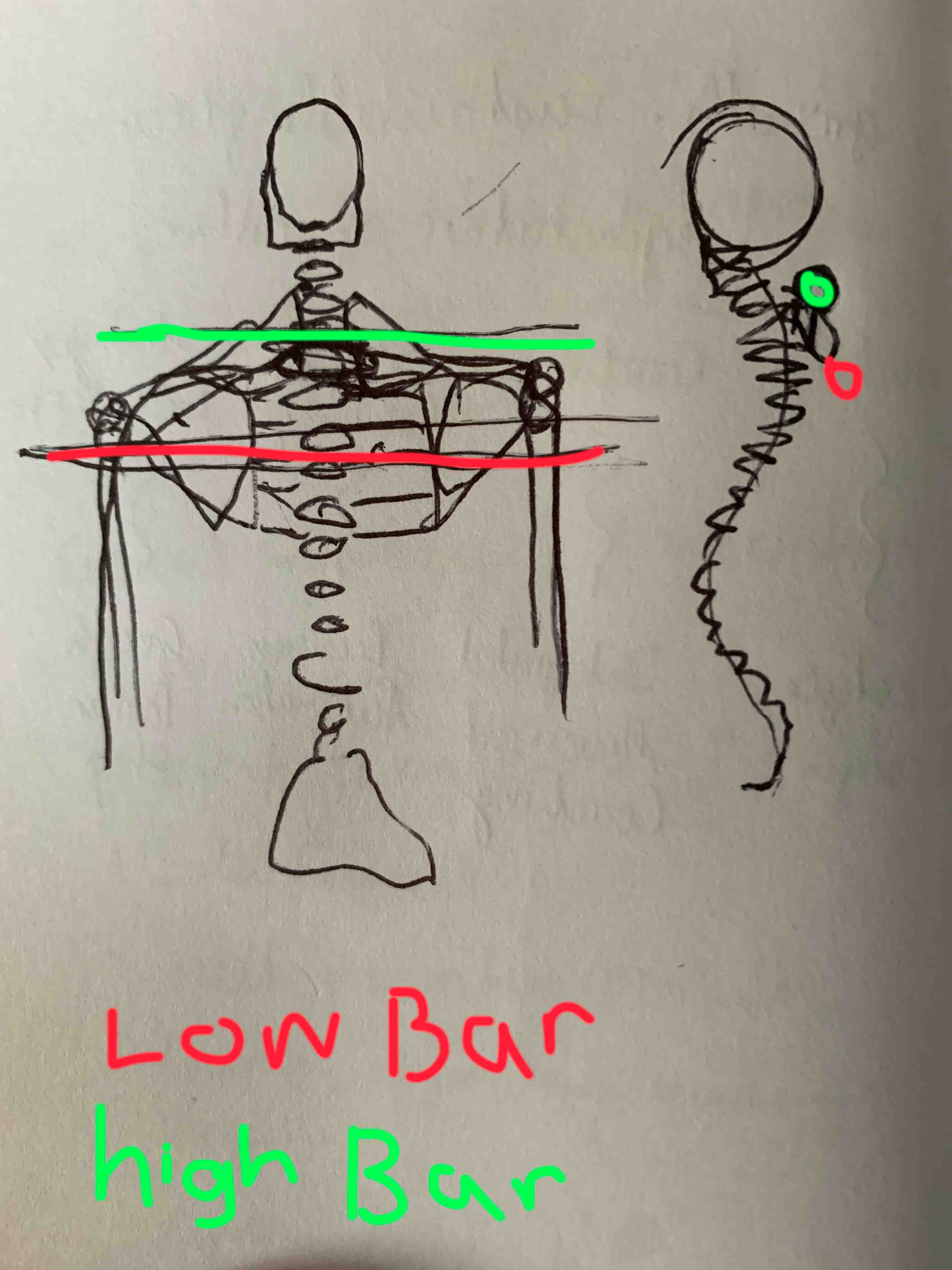

Now, let’s explore the differences between high bar and low bar squats and how they impact performance and safety.

High Bar Squat Basics

The high bar squat is the most commonly taught variation, especially in Olympic weightlifting and general strength training. In this position, the bar rests on top of the upper trapezius, just above the spine of the scapula. This setup keeps the torso more upright, emphasizing quadriceps engagement and a deep range of motion.

While the high bar squat allows for greater knee flexion and vertical torso positioning, it also presents risks for the neck and spine, particularly when form deteriorates under heavy loads. The main concerns include:

- Increased Neck Compression: Placing the bar higher on the traps can exert downward force on the cervical spine, leading to discomfort and possible nerve impingement over time.

- Shearing Forces on the Spine: As lifters lean forward (often due to weak core stability or ankle mobility restrictions), the bar may shift pressure to the lower cervical and upper thoracic vertebrae, increasing strain on the spine.

- Excessive Forward Lean: Poor mechanics—such as a lack of ankle mobility—can force lifters to compensate with forward lean, then shifting stress to the lower back rather than evenly distributing the load.

When performed with proper technique and adequate mobility, the high bar squat is highly effective. But for individuals with neck pain, past spinal injuries, or mobility restrictions, switching to a low bar squat may be a safer option.

Introducing the Low Bar Squat

The low bar squat differs in bar placement and mechanics. It offers a more hip-dominant movement. Here, the bar is positioned lower on the back and rests below the spine of the scapula, across the rear deltoids. This placement changes the squat’s movement pattern, shifting more emphasis to the posterior chain (glutes, hamstrings, and lower back).

Key Benefits of the Low Bar Squat:

- Reduced Neck and Spinal Strain: Since the bar sits lower, there is less direct pressure on the cervical spine, minimizing the risk of nerve compression and shear forces.

- Stronger Hip Engagement: The lower bar position allows for a greater hip hinge, activating the glutes and hamstrings more effectively than the high bar squat.

- Better Balance for Those with Forward Lean: The bar's position moves the center of gravity further back, making it easier for lifters with mobility restrictions or long femurs to maintain proper squat depth without excessive forward lean.

- Increased Lifting Capacity: Because of the improved mechanical leverage and posterior chain involvement, most lifters can handle heavier loads in the low bar squat compared to high bar.

However, the low bar squat requires more upper back and shoulder mobility to hold the bar securely. This makes it a less comfortable option for those with tight chest or shoulder muscles.

That said, improving flexibility in these areas can make the low bar squat an excellent alternative for reducing spinal stress and maximizing strength output.

Common Mistakes and Fixes

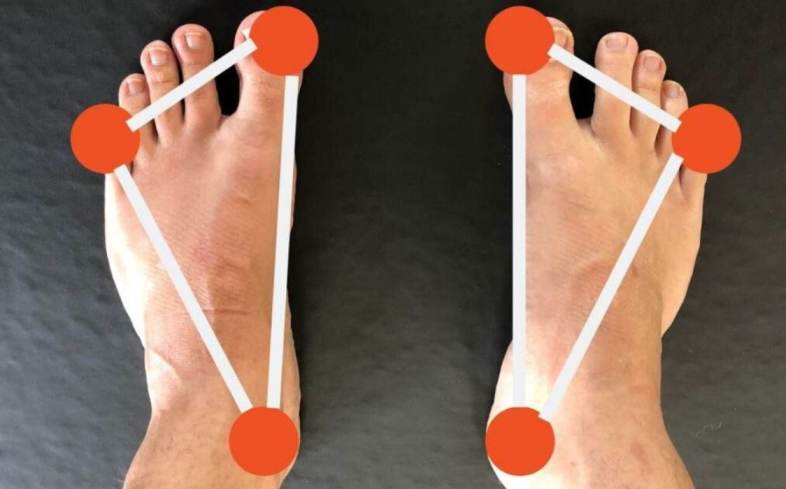

Weight Distribution and Bar Path

The Mistake:

Many lifters let their weight shift too far forward, causing excess pressure on the knees and lower back. This often results from weak posterior chain muscles, ankle mobility restrictions, or improper bar positioning.

Why It’s a Problem:

- Forward weight shift disrupts balance, increasing the risk of knee pain and injury.

- Excessive forward lean forces the lower back to compensate, straining the spine.

- Poor weight distribution reduces power transfer, making the lift inefficient.

The Fix:

- Evenly distribute weight across the foot—heels, balls of the feet, and toes (the "tripod" foot position).

- Paul Chek’s Trick: Lift your toes slightly inside your shoes. This shifts weight toward the heels and midfoot, preventing excessive forward lean.

- Keep the bar over the midfoot throughout the lift to maintain a stable bar path.

Neck and Spine Safety

The Mistake:

In high bar squats, improper posture and excessive forward lean increase shearing forces on the cervical and thoracic spine. Many lifters crane their neck up or excessively flex their spine under heavy loads.

Why It’s a Problem:

- The bar pressing into the C7-T1 vertebrae creates nerve compression and inflammation.

- Poor form shears the vertebrae forward, increasing the risk of long-term spinal instability.

- Weak bracing mechanics amplify lower back stress.

The Fix:

- Proper Bar Placement: Keep the bar resting firmly on the traps (high bar) or rear delts (low bar)—not pressing directly against the spine.

- Neutral Neck Position: Keep the chin slightly tucked, looking forward (not up).

- Bracing Before Each Rep: Engage the core and lats to stabilize the spine and reduce strain on the neck.

Mobility Challenges

The Mistake:

Limited mobility—especially in the ankles, hips, and shoulders—restricts depth and form. Tightness often leads to butt wink (lumbar rounding), forward lean, or knee valgus (knees caving in).

Why It’s a Problem:

- Poor mobility limits squat depth, reducing muscle activation.

- Butt wink increases spinal stress, heightening injury risk.

buttwink vs no buttwink

- Tight shoulders/chest make it difficult to maintain bar control, especially in low bar squats.

The Fix:

- Ankle Mobility Drills: Perform wall ankle stretches, weighted ankle dorsiflexion drills, and deep squat holds.

- Hip Openers: Use couch stretches, 90/90 hip rotations, and pigeon pose to improve hip mobility.

- Thoracic and Shoulder Mobility Work: Incorporate banded pass-throughs, overhead wall slides, and chest openers to improve low bar squat positioning.

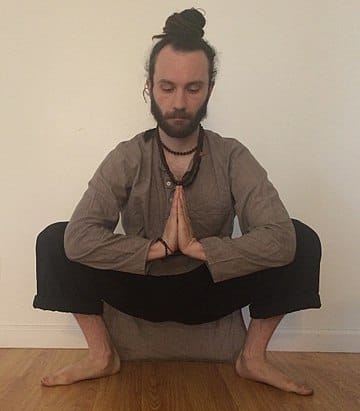

Reflections

Drop into a deep squat, feet flat on the ground. Feeling stressed? Drop into a squat, slow your breath. Feeling tight? Sink in deeper, let your hips open. Feeling disconnected? Squat, feel your feet on the ground, and remember where strength begins.

Let your hips sink between your heels.

Keep your chest lifted, your back engaged but not rigid.

Breathe. Settle into the moment.

Let gravity do the work, it’s about allowing the body to stretch, decompress, and find stability in stillness.

kiss kiss,

Tarkan